The Glory of God in the Byzantine Liturgy

When perceived through the divine things, the ‘radiant splendor’ of the rites performed is made manifest to them in due measure…

St Maximus the Confessor, Mystagogy, 2019: 48-49.

Does the splendor of the Byzantine Liturgy belong to aesthetics? Is Hagia Sophia a work of art? Is the Liturgy a drama?

The splendor of the Byzantine Liturgy is an image (εἰκών) of the glory of God and of His redeeming work. The Liturgy is a visible work of God (θεουργία) rendered in cooperation with humans for their benefit. Since it is a divine work, it must be splendid and majestic, exhibiting God’s glory and warranting our praise (ὑμνῳδία).

The Israelites referred to the presence of the LORD (YHWH) as the glory of God (כָּבוֹד, kevod) (I Sam 4.22, 6.5, Isaiah 6.3, 60.19, Ezek 1.9-11, 8.4, 9.3, 10.19, 43.2, etc.). God Himself is so awesome and transcendent that every time His name was written in the scroll the scribes added the vowel sound for Lord (Adonai) under the tetragrammaton, YHWH, so that the name YHWH would not be uttered. So awesome and transcendent God was, even His Name could not be said other than as “Lord.” Otherwise, His presence could only be referred to as glory. To see the glory of God, then, is to know/experience his presence. When God abandons his Temple, for example, it was described as the departure of his Glory.

Similarly, Pseudo-Dionysius was fully aware of God’s utter transcendence when he said:

We must not then dare to speak, or indeed to form any conception, of the hidden super-essential Godhead, except those things that are revealed to us from the Holy Spriptures.

The Divine Names (“DN”), 588A. The Dionysian phrase ‘super-essential’ (ὑπερούσιος) means ‘beyond being.’

Even though God is beyond being (i.e., not definable, confinable, circumscribable, measurable, or understandable in terms of any being), He is not aloof, remote, or unreachable, however. He gives signs (symbols) to signify His presence, His work, His love for us. He gave us His Son. He gave us his Scripts. He give us these, because He wants us to join Him and participate in Him through these symbols. For these symbols enable us to be lifted up to Him and participate (μετουσία) in His reality, have communion (μετουσία) with Him, and be His partners (μετουσία)—as much as we are capable—so that we may be in His presence and see His glory.

But in what sense do we feel his presence and see his glory? How can a finite being participate (μετουσία) in the Infinite, in His being/act/emanation/procession (πρόοδος)? In short, how can we recover the true “image of God” within us (Gen 1.26) that was meant to fundamentally connect us to God, the Creator? What is it about ‘becoming alike’ (ὁμοίωσις) that assimilates us to his presence without the pretense of becoming consubstantial (ὁμοούσιος) with Him?

The Scriptures say (in the form of symbols) that He comes in glory, clothed in a robe white as snow (Dan 7.9; cf., Rev 1.14) or “com[es] with the clouds of heaven” (Dan 7.13). Glory belongs to Him, like the glow of a fire that radiates, whether one sees it or not. God’s glory is manifest in the symbols of the Liturgy. In fact, the Liturgy itself is a symbol of God’s glory, whether one sees it or not, whether one attributes glory to Him or not in the morsel of the Bread and Wine carried “on the plate and in the cup.” The same is the case when we read the Scriptures; or when people saw Jesus. We humans often don’t see the glory of God in Jesus. It was the Roman centurion, of all people, who first acknowledged Him as the Son of God, as Jesus hung on the cross, as the earth shook and rocks split open (Mat 27.54). Many have missed seeing Him as the Son of God. Many still do. Nevertheless, He is who He is, whether we see Him as God or not. God’s glory belongs to Him intrinsically, in Himself.

Art or aesthetics, in contrast, belongs to human faculty and experience. The term ‘aesthetics’ comes from αἴσθησις, meaning ‘perception by the senses.’

The beautiful, according to Kant, is a judgment of taste when a subjective lawful interplay between imagination and understanding results in disinterested interest in restful and contemplative delight (KU 241, 252, 258); and the sublime is a judgment when a subjective lawful interplay is not possible due to the excessiveness of the object confronting the subject, but still resulting in an accord (despite the discordance) between imagination and reason. The result, says Kant, is the feeling of “a rapid alternation of repulsion from and attraction to … the same object,” which in turn reveals, according to him, our own sublimity as intelligible, rational being (KU 255-259). Whether in the case of the beautiful or the sublime, our mind judges it to be so in “restful contemplation” or in the sublimity of the accord overcoming the discord or repulsion (KU 258).

But God is neither beautiful nor sublime—contrary to Rudolf Otto’s claim in his book The Idea of the Holy, in which ‘holy’ for him means the sublime in the strict Kantian sense. God is not an aesthetic object.

Can we see God’s glory in our sense perception? Does it depend on our aesthetic judgment? No, because God’s glory is not an aesthetic object. Our senses cannot perceive His glory. For He exceeds the (aesthetic) judgment of our mind. Neither beautiful nor sublime, He is majestic, fearsome, just, merciful, loving, angry, forgiving, etc. These are not aesthetic categories. They are, for lack of better words, religious or moral categories. His glory lies beyond aesthetics.

When Isaiah speaks of seeing “the whole earth full of his glory” and his eyes seeing “the King, the LORD of hosts” (Isaiah 6.3, 4), he comes to see his own inadequacy, instead, in the end: “Woe is me! I am lost…” (6.5). Seeing God revealed his own gross inadequacy. An aesthetical experience does not operate like this. For no sense perception can convict one’s own inadequacy. In contrast, the glory of God convicts and humiliates oneself, revealing one’s gross inadequacy. No works of art can achieve such effects. For God’s majesty reveals our pride or vanity and crushes it.

At best, art can challenge our perceptual framework, gestalt, or paradigm of thought and outlook. But art lacks the power to transform us to the point of seeing our vanity and inadequacy. No art can humble the spectator. But the divine symbols can and do humble us and transform us into the likeness of God. For symbols are the Mysteries of the (hidden) divine reality and work that make us divine.. As such they have the power to uplift us to join, participate, have communion, and be partner with God in our capacity as His image. As such the divine symbols are not art objects, nor do they belong to our aesthetic experience. Rather, we can only approach them with fear and reverence. For we are drawing near the awesome presence of God.

Still, do the divine symbols reveal God’s glory? If so, how?

Seeing God, is to become God (without being consubstantial with Him), is to unite with Him in participation (μετουσία). Seeing, becoming, being united with God—all these are the same reality, in which we the finite participate in the Infinite, the reality and possibility which is grounded on the Incarnation Itself. If God can become a man, a rite/liturgy/symbol can be God’s act and providence in our midst and as such can reveal His glory. The Incarnation, the Symbol of all symbols, is also the principle of symbols that enables our participation in the Creator.

The Incarnation is the essence of Pseudo-Dionysius’ symbolic theology:

[Because] we also have been initiated[, we can] apprehend[…] these things in the present life (according to our powers), through the sacred veils of that loving kindness which in the Scriptures and the Hierarchical Traditions, enwrappeth spiritual truths in terms drawn from the world of sense, and super-essential truths in terms drawn from [b]eing, clothing with shapes and forms things which are shapeless and formless, and by a variety of separable symbols, fashioning manifold attributes of the imageless and supernatural Simplicity.

Dionysius the Areopagite, The Divine Names (hereafter ‘DN’), trans. C. E. Rolt, (London: Lewis Reprints Limited, 1920, 1940, 1971), 57-58; 592B.

The sensible symbols are not hinderance but indispensable vehicles, like veils, by which the Divine that transcends all senses, forms, and descriptions, is nonetheless enwrapped in the sensible and forms, clothing the Divine in “a variety of separable symbols.” Veils hide, to be sure, but in their hiding they reveal, like the veil of the bride. The bread is not a flesh but is the Flesh that clothed the Word. The bread is the Bread. This is enigma, aporia, and the divine mystery of the Symbol—ineffable, “beyond comparison,” beyond reason, exceeding the limits of reason. It is so in Itself. God is in the Flesh, in the material, in the souls, “through all and in all” (Eph 4.6). Our reason, perception, experience—all must be transformed in order to see God, to participate in Him, and to become like Him. Nothing can make this happen, except through the work of God being performed in cooperation with us. We participate (μετουσία) in Him, with Him, for Him in His service (Liturgy).

In short, the liturgy is nothing but our participation (μετουσία) in God’s act (θεουργία). We cannot reap the benefits of God’s (redeeming) act without our participation in that act. “Liturgy is the thing,” I want to say, altering Hamlet’s line: “Play is the thing.” By a play Hamlet hoped to reveal the truth about his adulterous uncle, the king, but failed. A play is not God’s work; and liturgy (τελετή, rite or initiation) is not a drama.

Liturgy is God’s providential energy/work in symbolic human ritual. As such it is the (divine) reality at work, where God’s will is done on earth as it is in heaven. Liturgy is where His Kingdom comes and is realized. This is what we participate in.

Participation in the Liturgy, then, is the key to becoming divine (θέωσις). Dionysius seems to agree, as he writes the following passage, which, Golitzin says, is “the most important passage in the entire [Dionysian Corpus]:”

It would not be possible for the human intellect (νοῦς) to be ordered with that immaterial imitation of the heavenly minds [i.e., the angels] unless it were to use the material guide that is proper to it, reckoning the visible beauties as reflections of the invisible splendor, the perceptible fragrances as impressions of the intelligible distributions, the material lights an icon of the immaterial gift of light, the sacred and extensive teaching [of the Scriptures] [an image] of the intellect’s inteligible fulfillment, the exterior ranks of the clergy [a image] of the harmonious and ordered state (ἕξις) [of the intellect] which is set in order (τεταγμένας) for divine things, and our partaking (μετάληψιν) of the most divine Eucharist [an icon] of our participation [μετουσίας] in Jesus Christ.

CH 121C-124A; Golitzin translation. Μετάληψιν refers to partaking of the Eucharist or food (See Lampe’s Patristic Greek Lexicon); whereas μετουσίας refers to the ontological ‘participation,’ ‘communion,’ and ‘partnership.’

It would be indeed impossible and unfair for us, if God had set up an order of things by which we can become divine without also providing us with the means to do so. Thank God, He did provide the means. They are, in Dionysius’ reckoning, the following “material guides:”

The visible beauties to lead us to the invisible splendor.

The perceptible fragrances (myron or unction) for leading us to “the hidden and sweet savored comeliness of God” (EH 473B) in His providential dealings with us and the universe.

The material lights for the immaterial gift of Light.

The teachings of the Scriptures for fulfillment of our soul.

The ranks of the clergy for harmonious and ordered habit of life.

The partaking of the Eucharist for participation in Christ.

All these “material guides” or symbols are provided for us. They are easy for us to use. All we need to do is to use them and leave the rest to God, so that his providentially working through them may leads us to Him.

The Glory of the Procession

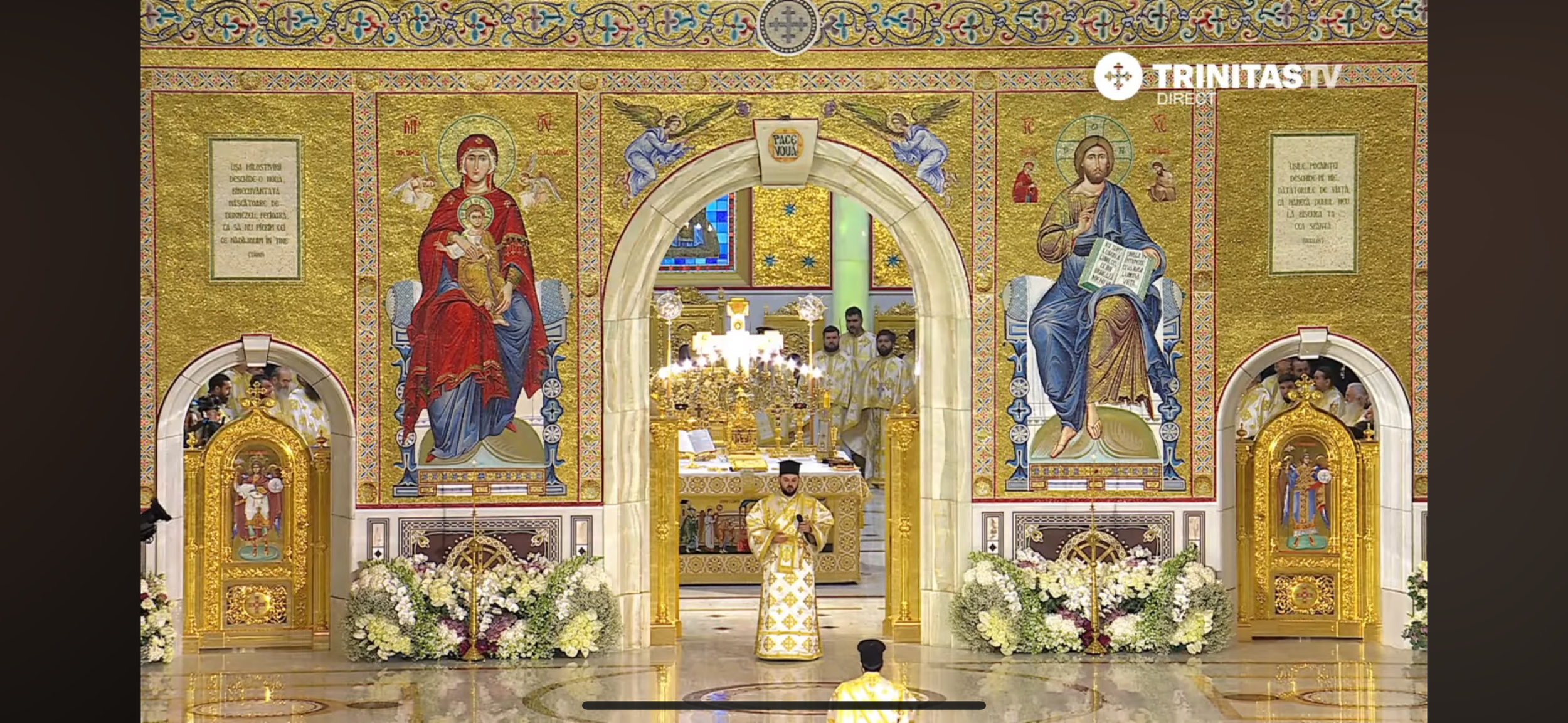

Although relatively late in its final development (circa late 6-century), the Great Entrance is arguably one of the most splendid parts of the Divine Liturgy.

The liturgy became more splendid, ceremonial took over the customs of the ceremonial of the imperial court, a conscious effort was made to provide in the liturgy a moving, symbolic, dramatic performance (Louth, 1989: 8).

The Great Entrance refers to the procession of the deacons and the priests carrying the Gifts to be transported to the sanctuary through the nave and to be laid upon the altar so that the Eucharistic rite (Anaphora) may begin.

The procession reflects the Byzantine sense of pageantry. The 10th century book on ceremonies, De caerimoniis, records the emperor participating in the Great Entrance procession as follows:

the sovereigns with lamps in hand march in front of the gifts, with the senators and chamberlains. The scepters and other accoutrements stand in their proper order and the sovereigns, going via the solea, stand outside the holy doors,…. The holy things, having arrived on the solea, pause, and the archdeacon comes and incenses the sovereigns, then the patriarch, and after him, the holy table. And thus all the holy things enter, and after all have entered, the sovereigns greet the patriarch and then go via the right side of the bema outside [the sanctuary] and enter the metatorion [a room in Hagia Sophia].

As quoted in Taft, 2004: 195.

Here in the procession the “King of Glory” (Ps 24.7-10) comes “in the disc and in the cup,” as Narsai of Nisibi put it, preceded by the emperor and his entourage holding lamps, and followed by the priests and other bearers of the liturgical implements.

Though seemingly a royal procession, the Great Entrance can be better understood, however, in terms of the Dionysian notion of the hierarchy (ἱερός + ἀρχή, ‘holy order’)—the term Dionysius invented, according to Andrew Louth (1989: 38).

Now, hierarchy has nothing to do with power or authority. Rather, it only pertains to assimilation (ἀφομοἰωσις, becoming like) and union (becoming one) with God by participation (μετουσία). The purpose of the hierarchy is strictly spiritual—imitation and illumination:

Hierarchy [ὶεραρχἰα] is … a sacred order [τἀξις ὶερὰ], knowledge [ἐπιστἠμη], and energy [ἐνέργεια] assimilating [ἀφομοιουμένη], as accessible as possible [ἐφικτὸν], to the likeness of God [θεοειδὲς] in connection with [ἀναλόγως] illuminations [ἐλλάμψεις]—illumination which itself is endowed [ἐνδιδομένας] from God—into upliftment [ἀναγομἐνη] toward God-imitation [θεομίμητον].

Dionysius, Celestial Hierarchy (CH), Ch. 3; 164D, translation mine.

It is the deacons and the priests who transports the Gifts, starting from the sanctuary (prothesis), going through the nave, and returning to the sanctuary to hand over the Gifts to the awaiting bishop. The function of each celebrant in each of their respective roles within the hierarchy is important, as their ranking dictates what roles they are to play in the Liturgy. The movement in the Liturgy starts from the lower rank and gradually elevates into the higher rank. For example, at the time of Hagia Sophia, the non believers and the penitents cannot enter the church but stand outside the narthex in the atrium. The patriarch or the bishop enters the narthex, holding the Gospel (book), as the choir sings antiphones, and brings the Gospel into the sanctuary in the procession called “The Little Entrance.” The Epistle and the Gospel are read in the ambo by the deacon(s); whereas the Eucharist is performed in Anaphora and communed inside the sanctuary by the Hierarchs and the priests before it is brought out to the nave (syntax) to be distributed among the faithful. According to Dionysius, the deacon is to purify the believers or the catechumens; the priest is to illuminate the baptized; and the bishop or the Hierarch is to perfect the rite/initiation by performing the rite of myron (the fragrant mixture of olive and balsamic oil). God’s re-generative bestowal of loving kindness emanates from the altar in the sanctuary to the nave, pulling or uplifting the faithful back into the divine presence in the circle of procession (πρόοδος) and return (ἐπιστροφή). Both the Little Entrance (in the Liturgy of the Word) and the Great Entrance (in the Liturgy of the Faithful) symbolize and re-enact the Dionysian circle of going out (emanation) and return.

In the following short description, Archbishop Alexander Glotzin, to my knowledge, best describes the procession of the Great Entrance to be understood as part of the Eucharist:

It is thus during the Eucharist—exiting the altar to cense the entire temple, reentering the altar, and, later, inviting believers to partake of the Gifts—that the bishop provides us with an icon of the divine procession and Providence.

Golitzin, 2013: 141.

For Golitzin the Great Entrance is a symbol of God’s work of providence, the salvific work that, as Dionysius puts it, “preserves all things in their proper places without change, conflict, or deterioration…” (DN 897A). The orderly procession in hierarchy is the very movement of God’s way of redeeming/restoring the world, by which all things are put in place as they should be in their “proper virtues” (DN 897B). To participate in the divine reality (God’s providential work) within one’s own proper place is to effectuate God’s work of re-creation, so that God will be “above all and through all and in all” (Eph 4.6; cf., I Cor 8.6) within their hierarchy. We do not transgress above or below ourselves in the hierarchy to participate in God’s work/energy/operation. Remaining within our proper place, we participate in His operation to the fullest extent possible within our own capacity (ἐπιτηδειότης, κατ’ όικείαν άναλογίαν).

To be within one’s own capacity but to be so fully and maximally is to be virtuous. This is what it means to participate (μετουσία, participation, partnership, communion (CH 305C, 308A)) within the hierarchy of God’s operation. Participation in the hierarchy includes participation in the ecclesiastical hierarchy—the only order (τάξις) we have. We can imitate angels but cannot participate in the celestial hierarchy. To do so would be to transgress our created order. It would be to sin and to “stumble upon into error or disorder and suffer a diminution of the perfection of [our] proper virtues” (DN 897B). Participation within the hierarchy is the only way in which we can reap the benefits of God’s providential work.

The Pageantry of the Neo-Platonism

Steeped in the intellectual climate of Neo-Platonism, as many of the early church fathers were, it is tempting to argue that Dionysius conceived the idea of hierarchy with the following passage in mind, written by Plotinus, the father of what we now call Neo-Platonism. In the passage, Plotinus speaks of a royal procession as follows:

… just as in the procession of a great king, the lesser come first, and the greater and more dignified come after them in turn, and those who are even closer to the king are more regal, and those next even more honored. After all these, the Great King suddenly reveals himself, with the people praying to him and prostrating themselves, at least those who have not already left, thinking that it was enough to see those who preceded the king.

Plotinus, Enneads 5.5.3; 2018: 586.

Here, the revelation of the Great King happens suddenly after the gradual splendor and dignity are built up in the procession. The progressive revelation of glory is interrupted by the sudden appearance of the Great King, whose glory is incomparable—so much so that people fall down in prayer and in prostration at the sight of him. But some miss the King, because they thought “it was enough to see those who preceded the king.” Some others who remained did not see the King either, because they were “praying to him and prostrating themselves” before the King when he passed them by. The sudden appearance of the King in glory compels the onlookers to prostrate in prayer.

Plotinus here is explaining by analogy the soul’s encounter with the One, the Good, as she ascends to the height. At the top of the ascent, the encounter happens “suddenly.” Because the One transcends all being below. But when the soul sees the Good “without seeing how,” she is united with the Good, while unable to distinguish herself from the Good itself. The soul joins the Good by becoming other than herself, as she becomes “beside [her]self.” In becoming identical with the Good, the soul loses its own identity, as Plotinus explains:

For the cognition or touching of the Good is the most important thing….

[…]

Someone actually leaving all learning, up to then having been educated by instruction, settles in Beauty. Up to then he thinks, carried along in a way by the wave of the intellect, and in a way raised on high by it, puffed up in a way, he sees suddenly without seeing how. The spectacle fills his eyes with light, not making him see something else through it. The seeing was the light itself. For in the Good there is not one thing which is seen, and another thing that is its light; nor is there intellect and object of intellect, but the radiance, engendering these things later, lets them be beside itself. It itself is only the radiance engendering Intellect, without being extinguished in the act of generation, but remaining identical. Intellect comes about because the Good is.

Plotinus, Enn. 6.7.36.

Light sparks light suddenly and without distinction. The union (between the cause and the effect) obliterates the distinction and identity. Such is the Neo-Platonic ascension of the soul to the One and becoming one with the One. In this stage, the soul is “release[d] from everything here [in the world below], a way of life that takes no pleasure in things here, the refuge of a solitary in the solitary” (Enn. 6.9.11).

Although Pseudo-Dionysius heavily borrows from Plotinus, he makes a crucial break from him: that one’s ascent to God is not a complete abandonment of one’s identity or everything worldly. In becoming divine, we do not become disembodied souls like angels. Rather, we sanctify and divinize everything that we are: the world and ourselves therein, our body and soul. We do not leave our bodies, we divinize them, as we divinize our souls. This is why the following phrases Dionysius repeats throughout his writings are important: “as much as suitable” (ἐπιτηδειότης, fitness, suitableness), or (to translate literally) “in proportion to and in accordance with one’s own home base” (κατ’ όικείαν άναλογίαν, analogous). We do not become angels or gods in imitating God (θέωσις). Rather, we remain human—fully human in the way we are supposed to be within the divine order (τάξις) that God has set up for us, i.e., within the ecclesiastical hierarchy (in which both a king and a monk belong to the same order of laity).

The sudden brightness of the divine glory is associated with the Incarnation. In his Letter III, he writes:

‘Suddenly’ [ἐξαίφνης] is that which, contrary to expectation, and out of the, as yet, unmanifest, is brought into the manifest. […] … the Superessential proceeded froth out of the hidden, into the manifestation amongst us, by having taken substance as man. But, He is hidden, even after the manifestation…

Letter III, 1069B.

The glory of God manifests suddenly, beyond any expectation, beyond any understanding, beyond any knowledge. Christ makes a sudden appearance (though still hidden) at his birth (Lk 2.13), at the commencement of his earthly ministry (Matt 3.16), at Mt Tabor when he was transfigured (Matt 17.3, 5), and in his risen Body on the road to Emmaus (Lk 24.29-31). Likewise, He makes a sudden appearance (though still hidden) as He is carried “on the plate and in the cup.” Our partaking of the Eucharist symbolizes (thus makes it real) our seeing Christ, “the Light of the Father” (CH 121A). For this reason, at the first moment when the communion is completed, the choir sings: “We have seen the true Light…”

But seeing the Light is becoming the light oneself, like fire sparking fire. Here, the cause becomes indistinguishable from the effect. Once illuminated, one becomes herself the source of illumination for others. Like the spark of fire, illumination is sudden.

The Sudden Mystical Encounter

In Mystical Theology, Dionysius likens the sudden encounter with God with Moses’ speaking with God at Mt Sinai and hearing the voice of God “out of the darkness” (Deut 5.22-23; Exod 19.16-20, 34.29-35). “At the topmost pinnacle of the Divine Ascent,” Dionyisus writes, Moses “meets not with God Himself… but the place wherein He dwells” (MT, 1000D). It is here, however, where, according to Dionysius, Moses “plunges … unto the Darkness of Unknowing” (MT, 1001A). The plunge is sudden. Dionysius writes further:

… unchangeable mysteries of heavenly Truth lie hidden in the dazzling obscurity of the secret Silence, outshining all brilliance with the intensity of their darkness, and surcharging our blinded intellects with the utterly impalpable and invisible fairness of glories which exceed all beauty!

MT, 997B.

Note the pairs of opposites here: “the dazzling obscurity of the secret Silence,” the brilliance of the darkness, the “invisible fairness of glories which exceed all beauty.” The silence that dazzles, the darkness that is brilliant, the invisible beauty that exceeds physical beauty—words cannot do justice to the Mysteries of divine reality. But these pairs of opposites suggest suddenness of the encounter with the incomparable, with the Beyond. Still, however, we are capable of participating in this Mystical Reality, beyond our intellect and language—to the extend that we are capable. But I want to focus on the “secret Silence” and on “the intensity of … darkness” that Dionysius speaks of.

Golitzin notes a curious Syriac equivalent to Greek ἐξαίφνης (suddenly). Citing A Compendious Syriac Dictionary (Oxford, 1903, 1990), he observes that the Syriac word, men shelya—the equivalent of ἐξαίφνης—has meanings associated with ‘rest,’ ‘silence,’ and ‘stillness,’ which is “usually connected in Christian Syriac with the hermits, as in ἡσυχία [stillness] in Christian Greek” (Golitzin, 2013: 49). In Syriac, then, ‘suddenly’ is associated with ‘rest,’ ‘silence,’ and ‘stillness’ that is associated with the hermetic stillness in their experience with God. All three words (rest, silence, and stillness) are used one way or another to describe the state of the union with God in many patristic writings (including Palamas (d. 1359) and even in Augustine (d. 430) as well as in Plotinus, when he too describes the soul’s union with the One with the adjective ἐξαίφνης (suddenly) (Enn. 3.8.6, 5.3.6.15, 5.3.7.13-16, 5.5.3, 5.5.7-8). As we have seen above, the Great King appears “suddenly” in his procession accompanied by his entourage. When neither affirmation nor negation is adequate, silence befalls. Such is the mode in which one may encounter God, who comes nonetheless “on the plate and in the cup.”