PROTHESIS

(The Table of Offering)

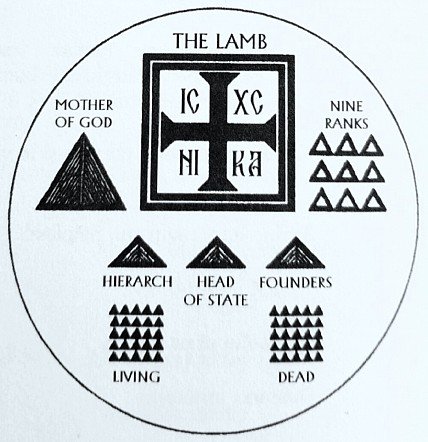

In the Orthodox liturgical usage, the word ‘prothesis’ refers to a place of offering preparation, a small table or counter in an enclosure (beside the alter in the sanctuary nowadays), on which the prosphora (the bread) is prepared (in the fashion shown in the diagram) and the wine poured into the chalice during the Prokomidi (προσκομιδή, oblation)—a miniature rite that precedes the Divine Liturgy proper. Once the elements are prepared, they are later brought to the altar in a procession called “the Great Entrance,” which some Orthodox churches still practice in its full splendor. The elements picked up and carried by the deacon and priest exit through the northern door of the iconostasis (since the prothesis is behind the iconostasis), move through the nave, enter into the sanctuary (as received by the bishop, if presiding), and reach the altar, upon which they are laid on a cloth-icon called antimension (that has the bishop’s signature and a saint’s relic affixed to it), the authority upon which alone the priest is authorized to perform the Eucharist. The Eucharist is performed during the latter part of the Divine Liturgy called Anaphora (ἀναφορά, ‘rising of a sign’), in which the Elements are raised to God and consecrated (i.e., changed into the Body and Blood of Christ and offered).

The word ‘prothesis’ (πρόθεσις) actually means ‘offering,’ ‘(the loaves) laid before,’ ‘shew-bread’ as in LXX 1 King 21.6(7) (“the loaves of the presentation… the loaves of the presence…”). Prothesis also means: ‘a placing in public.’ ‘laying it out,’ ‘public notice,’ ‘statement of a case.’ (Lampe defines it, among others: ‘table of shewbread,’ ‘setting forth of eucharistic offering,’ ‘offertory,’ ‘eucharistic elements as set forth.’ Hence, ‘a table of offering’ is a proper translation of ‘prothesis’ (David L. Frost, The Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, 2015)). As such, it is closely associated with προτίθημι, meaning “to place before, to propose, to set before oneself, hand over for burial, set up, institute, fix, set, setting before oneself; lay out (a dead body), let (it) lie in state.” St Germanus (d. 740) uses the word in reference to Christ’s sacrifice at the Eucharist: “Christ sacrifices [ζωοθυτούμενος] His flesh and blood and offers [προέθηκε] it to the faithful as food for eternal life” (Ecclesiastical History and Mystical Contemplation,” paragraph 4 in P. Meyers’ translation, 1984: 59). I will come back to this quotation later.

Even though the ritual acts that the priest performs in the Proskomidi are highly symbolic (connecting Christ’s physical crucifixion events to the actions performed in the rite (“As a sheep led to the slaughter….;” “Sacrificed is the Lamb of God, who taketh away the sin of the world, for the life of the world and its salvation…”), the rite is invisible from the people in the nave, as it takes place behind the iconostasis on the ‘table of offering’ in the periphery of the sanctuary— or (in Hagia Sophia) in skeuophylakion (treasury) (“the small rotunda…, a separate edifice adjacent to the church, located just off the northeast corner of Hagia Sophia” (Taft, 1980/1981: 49))—and mostly performed by the priest alone, while the psalms are chanted by the canter in the choir loft.

The Proskomidi is relatively late development, circa 730. It began as a simple preparatory exercise (“without ceremony or fuss” (Taft, 2004: 19)) to prepare the prosphora (bread offering) and to pour wine into the chalice. According to Taft, even during the time when St Germanus was the Patriarch of Constantinople (715-730) the Proskomidi in Hagia Sophia was not fully developed (Taft, 1980/1981: 49). Taft writes:

The people bring to the priest their prosphora with a list of the living and dead for whom they wish [the priest] to pray, whenever they happen to arrive in church. These gifts remain in the skeuophylakion or prothesis until after the Liturgy of the Word, when they are then transferred to the altar in the Great Entrance.

Taft, 2004: 34.

The prothesis, then, is not (the place of) the actual offering/sacrifice (προσφέρειν)— i.e., the Eucharist itself, which is performed on the altar in the sanctuary—as the bread and wine have not yet been consecrated as the Body and Blood of Christ. The Proskomidi performed at the prothesis only prepares and anticipates what is to come. The Liturgy is yet to begin.

In the coptic Orthodox churches, however—as I have observed personally—the Proskomidi is programed into the early part of the Divine Liturgy itself and is performed on the ambo, visible to everyone in the nave.

Is the Eucharist a Heavenly Banquet?

St Ambrose (d. 397), to my knowledge, was the first to interpret the Eucharist bread as the ‘daily bread’ (τὸν ἂρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον) sought in the Lord’s Prayer. He wrote:

Christ, then, feeds His Church with these sacraments, by means of which the substance of the soul is strengthened.

On the Mysteries, Ch 9, par. 55; Ambros, 2016.

Επιούσιος means ‘sufficient for the day’; thus the coinage in the Lord’s Prayer means ‘the necessary, daily, and sufficiently sustaining bread.’

In the same vein St Germanus says, as already quoted:

Christ sacrifices [ζωοθυτούμενος] His flesh and blood and offers [προέθηκε] it to the faithful as food for eternal life”

P. Meyers, 1984: 59.

Both Ambrose and Germanus probably had in mind John 6.51:

I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever, and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.

This is probably the origin of the idea of the Eucharist as a heavenly banquet. But is the Eucharist a heavenly banquet? Does the Liturgy imitate the heavenly reality? Or, does it bring down and stamp (ἀποτυπόομαι) heaven reality on earth?

Jesus instituted the Eucharistic rite as a paschal meal, in which the deliverance of Israelites from the angel of Death and—by extension—from Egypt is remembered (Exod 12). In the same way, our deliverance from the power of death by the blood of Christ and by His Resurrection (“conquering death by death”) is to be remembered and actualized every time we celebrate the Lord’s Supper (Lk 22.19, 1 Cor 11.24-25).

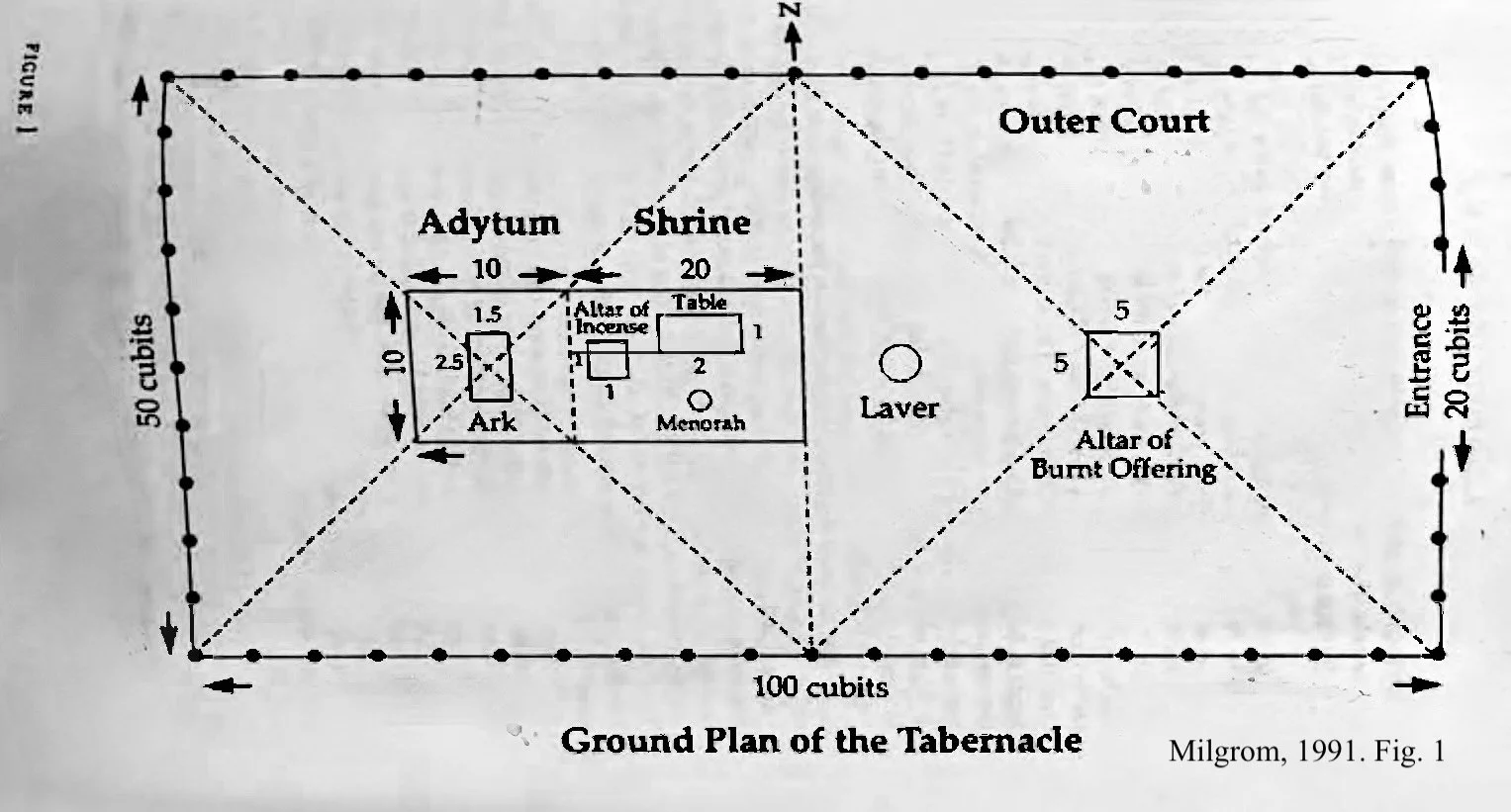

The Hebrew word פֶּ֥סַח, pesah, translated as πάσχα in LLX, means ‘protection,’ as in Exod 12.27, Isaiah 31.5; see Milgrom, 1991: 1081.

‘Passover’ ‘atonement,’ and other terms are words invented by William Tyndale (d. 1536). The word ‘banquet,’ first recorded in 1450-1500, originated from Italian banchetto, meaning ‘table.’

The Catholic churches call the liturgy ‘mass,’ which is “first recorded in 1350–1400; Middle English masse, from Latin massa ‘mass,’ from Greek mâza ‘barley cake,’ akin to mássein ‘to knead.’”

Christ’s blood protects us from the bondage of death; His Body is laid on the eucharistic table as sacrifice/offering. The primary meaning of prothesis (πρόθεσις, ‘offering’) is to offer the animal flesh to God in sacrifice, as in προσφέρειν, ‘to bring to,’ ‘present,’ ‘offer,’ ‘set food before one.’ Offering is the essence of sacrifice, not eating (in a banquet). (In ancient Greece feasting followed the sacrifices. But, strictly speaking, sacrifice itself is not feasting.) Slaughter, too, is not the essence of sacrifice. To sacrifice does not mean ‘to kill’ but to offer gifts or to bring the offering to God. The Israelites not only offered animals but also grains, wine, bread as thanksgiving sacrifices. These do not involve slaughter.

Jesus offers his Body as heavenly manna to demonstrate his act of offering in sacrifice, as in Jn 3.16 (“God gave ….”). Like Christ’s descent (Phil 2.7-8), the mannas came down from heaven. The mannas in the dessert were not associated with ‘feasting’ or enjoyment thereof as in a banquet. Jesus’ metaphor of eating (Jn 6.51), furthermore, refers to the idea of union rather than having a banquet. By eating one becomes what one eats; and by eating together, a bond is formed among the participants at the table. The idea of union that is emphasized in the Eucharist, moreover, is the union between God/Christ/the Holy Spirit and us, a communion with the Holy Spirit, not so much the union among the faithful, as Augustine emphasizes (Sermon 272, 1993: 300-301; see below.). St Paul’s emphasis on the unity among the members of the church as belonging to one body of Christ is not directly associated with the Eucharist but with talents and functions of each member (Rom 12.5; I Cor 10.16; I Cor 12.12-27). Both baptism and the Eucharist refer to our unity with Christ, not to unity among the faithful.

Notes

‘To celebrate’ (τελετουργέω) the Eucharist does not mean to enjoy it as if in a banquet. Rather, it means ‘to complete.’ To complicate the matter, however, τελετή, means: “rite esp. initiation in the mysteries; a festival accompanied by mystic rites; a priesthood or sacred office.” To these, Lampe adds: “initiation of sacramental rites.” But, again, a festival follows the sacrifice; it is not the sacrifice itself.

St Augustine’s Sermon 272

In his Sermon 272 Augustine explains the Eucharist as follows: “Remember: bread doesn’t come from a single grain, but from many. When you received exorcism, you were ‘ground,’ When you were baptized, you were ‘leavened.’ When you received the fire of the Holy Spirit, you were ‘baked.’ […] In the visible object of bread, many grains are gathered into one just as the faithful .. form ‘a single heart and mind in God’ [Acts 4.32]. […] This is the image chosen by Christ our Lord to show how, at his own table, the mystery of our unity and peace is solemnly consecrated.”

Thus, for Augustine, the bread consumed at the Eucharist indicates the unity among the members of the Church, the Body of Christ. With Augustine, the Russian Orthodox theologians tend to emphasize the unity of the Church in association with the Eucharist.

Incidentally, Augustine hardly uses the word ‘symbol’ but prefers to use ‘image.’ This has a significant consequence in terms of understanding sacraments. It must be noted that Augustine’s notion of sacrament is very different from the Syriac notion of symbol (raza), which is frequently translated as ‘sacrament.’ But Augustine’s understanding of ‘sacrament’ is close to the Platonic notion of ‘image’ or ‘representation.’ In the Platonic sense, a sacrament would represent or point to a deeper but different reality of God and His work that cannot be represented, visually or intellectually, by an image. The concept of unity, says Augustine in Sermon 272 as quoted above, is visually illustrated in the Eucharistic bread, as it is with the wine analogy (which I skipped and did not quote).

In contrast, in the Syriac notion of symbol, as in Neo-Platonists’ usage, including Dionysius the Areopagite, the divine reality (which is by definition a mystery) is contained in the visible symbol, objectively. Such an objective reality is what a sacrament is supposed to contain or embody, as it became to be so understood eventually by the Latin Church, including Augustine himself. In other words, Augustine, too, had the stronger (Syriac) sense of sacramental reality. He apparently said somewhere, I am told, that “Christ is sacrament.” Nonetheless, Augustine more often than not resorted to the idea of sacrament more closely associated with the Platonic sense of ‘image’ (εἰκών) or a sign. In this sense, a sacrament is a sign, something that represents the unrepresentable reality. A sign can never be the Thing itself, the divine reality/Mystery Itself that a symbol is in Syriac (raza). The Latin word symbolum means: “The brand, the mark, the emblem, by which someone is to be recognized or identify themselves.”

Thus, the unity Augustine speaks of in his Sermon 272 regarding the Eucharistic bread is arguably not present in the Bread as Christ is sacramentally. For Augustine the bread illustrates the unity of the Church but cannot be the unity itself, even though he would say that the Bread is the reality/Mystery of Christ Itself (sacramentally speaking). In other words, the Bread is not the unity of the Church; it is Christ Himself. The Bread can represent the unity of His Body, the Church.

Such allegorizations (or figurative use) of symbols/sacraments as in Augustine’s Sermon 272, however, is also present in St Germanus’ tract written for catechumens. (Germanus was the ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople between 715 and 730).

The evolving liturgical symbolism in terms of the Gospel narratives of historical Jesus (in allegorical or figurative functions)—the development Robert F. Taft terms the “incarnational realism”—was an inevitable, though unexpected, consequence of the churches’ struggle against iconoclasm (Taft, 1980/1981: 55, 59, 70; P. Meyer, 1984: 50).

The emphasis on the indispensable role of icons in the life of the Church produced an unexpected side effect: the equal emphasis on the historical life and passion of Christ.

The turn to “incarnation realism” had already begun, however, when the issuance of the Peace of Constantine (313) resulted in hallowing of the holy places in Jerusalem, such as the Holy Sepulcher (326-335), or the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem, Palestine (326-330).

Concomitantly, the Arian controversy erupted, necessitating the assembly of Nicene Council (325), in which the divinity of Christ was upheld, while His human nature was also affirmed. This resulted in a re-interpretation of the Liturgy, in which, as Taft writes, “Antiochene liturgical writers elaborated their symbolism of the liturgy as a representation of the human saving work of the man Christ” (Taft, 1980/1981, 70).

The iconoclasm erupted in 726 when Emperor Leo III degreed against religious images.

Germanus spoke against iconoclasm at the iconoclastic counsel of 754, which condemned him:

we draw [in the icon] the image of [Christ’s] human aspect according to the flesh…[…] we represent the character of His holy body on the icons, and we venerate and honor them with the reverence due to them…”

P. Meyers, 1984: 49.

St John Chrysostom (d. 407) was one of those Antiochenes, who is said to have brought the institution narrative of the paschal supper into the Liturgy of Constantinople (in Hagia Sophia, where he was the Patriarch for a year between 397-398), as it is inserted in the section called Anaphora (“… in the night that He was given up… He took bread … He gave it to his holy disciples and apostles, saying: Take, eat; this is my Body….” See Liturgy of the Faithful).

Taft further writes: “Antiochene liturgical explanation begins to elaborate a symbolism of the presence of the saving work of Christ in the ritual itself, even apart from participation in the communion of the gifts” (1980/1981: 69). Thus, for example, the altar is symbolized as Christ’s burial cave, out of which He arose in Resurrection, as Germanus interprets (“The altar [is] the holy tomb of Christ” P. Meyers, 1984: 61; translation altered)). Germanus also interprets the symbolism of the altar as the source of the divine power:

The altar is and is called the heavenly and spiritual altar, where the earthly and material priests who always assist and serve the Lord represent the spiritual, serving, and hierarchical powers of the immaterial and celestial powers, for they also must be as a burning fire.

P. Meyers, St Germanus of Constantinople: On the Divine Liturgy, 1984: 61.

To say that the altar symbolizes the tomb of Christ’s burial and Resurrection, and thus the source of spiritual power, is to remove the symbol of the Eucharist one more level further. If the altar is the source of the power of resurrection or spiritual power, how are we to venerate it? Should the altar itself be treated as a symbol in the strong sense? Does it have the power of resurrection?

Furthermore, are we not united with the Risen Lord, already participating in his Resurrection, just as we are in his Death—daily and every time we partake of his Body?

The altar symbolized as Christ’s tomb and as the source of His resurrection, in my opinion, get in the way of our direct participation in Christ’s Death and Resurrection. Why do we need another symbolism (of altar) in order to understand the symbolism of Christ’s death and resurrection in baptism and the Eucharist?

The alar, which is a part of the sanctuary, should be treated as the essential part of the symbols. It is a part of the Liturgy, just like incense, the Gospel book, iconostasis. Where would the bread and wine be laid to be offered, if there were no altar? The altar, like icons, should be respected, just as the sanctuary is, and just as the church building as a whole is. But we should not assign any more significance to it than that. Otherwise, we will have proliferation of symbols and their meanings that are not indispensable or necessary or may conflict with other competing meanings, thus creating confusion rather than edification.

For St Paul, the symbolism of baptism (to die and to live in Christ, as one is submerged in and rises from the water) is enough. Eating the Bread and drinking the Cup is enough. We do not need another layer of symbolism assigned to the altar. Of course, the altar is physically necessary and should be venerated, like the icons. But we should not elevate the altar to the level of a symbol in the strong sense of the term, to the level of a sacrament.

The “incarnational realism” invariably leads to erosion of the liturgical symbolism; because the divine reality that the liturgical symbols contain and produce in the Liturgy is neither the historical events themselves, nor the Scriptural narrative thereof, nor the visible ceremony itself with all of its robes and implements.

When we are called to “draw near in fear of God, and in faith and love”—as we are in the Liturgy— to receive the Elements, are we called to historical Jesus at Golgotha or to Christ Himself in communion (κοινωνία) with Him and His Spirit? Does the Liturgy initiates us directly into the divine Mystery itself or does it recalls and re-enacts the historical events of Christ? Is the Divine Liturgy to be understood as a drama of salvation history as recorded in the Scriptures, or is it the reality of (the work of) God’s salvation itself here and now? The symbol is the divine reality in and of itself.

The Liturgy does not merely re-enact the historical event of Christ. It actualizes Christ event here and now in what C. H. Dodd called in 1935 the “realized eschatology.” Christ’s birth, death, and resurrection actually happen during the Divine Liturgy, as they are symbolized therein. This is so because the divine symbols are the divine reality in and of itself.

Related topics:

Back to Proskomidi.

Back to top.